Sudan: Palliative Care and the News of Reality, by Dr Mohja Khairallah

![]() Cairdeas

Cairdeas

![]() 28th April 2023

28th April 2023

Dr Mohja Khairallah is a family physician and palliative care specialist at the Khartoum Oncology Hospital in Sudan. She founded the Comboni Palliative Care Volunteers (CPCVs) and recently led palliative care trainings in Mauritania through Cairdeas Sahara. During this last week of April 2023, she shared her observations and reflections on the need of palliative care – and peace – in Sudan.

Note that accompanying photos are taken before 2023 during a time of peace in the Khartoum area.

Since 15th April (the first day of our social unrest) I've been locked in my small town 40 km south of Khartoum, Sudan where I live with my family, and we are all safe physically (thank God). I have cared for three patients with different neurological conditions at their home, with no resources, in this time. Unfortunately, I lost two of them because they couldn't get the hospital care (ICU) that they needed; we thank God the third one is stable and well. The current need for palliative care is the greatest ever.

1. For cancer patients:

Unfortunately, opioids have not been available for the last 4 months, and now even the access to the alternative available pain killers, cancer treatment, and face to face support are no longer possible, especially in the capital city.

2. For patients with medical emergencies, injuries, and chronic diseases:

Most of the hospitals are out of service or closed, due to lack of medicine, that the staff cannot reach the hospitals and insecurity. Death is everywhere, with very sick patients who have left the hospitals, HDUs & ICUs and have died in the community (homes).

3. The death of innocent people and the smelly dead bodies thrown in the streets cause a lot of pain and worries for families and communities.

4. Lack of basic life needs (water, food, security) makes people terrified. Now, a lot of Sudanese are leaving the country to face a new suffering of becoming refugees.

5. Telemedicine is no longer an option to provide palliative/medical care since the networks and tele. companies have no /or interrupted services.

I've tried to help my people and wrote a letter to our local community and army leaders asking for their support, protection, and contribution in establishing a volunteer clinic for patients with chronic diseases (including cancer). This clinic would aim to provide simple palliative and medical care and follow-up services safely, while reducing the workload for the only functioning hospital in the area.

But as you know, a such process to set up a volunteer clinic can take time, especially in times of war. Yet I am waiting for their positive response.

Lately I have noticed in myself and most of my friends, that watching news on some channels have increased our sadness, tension, and fear.

After a while we discover that the news channels only amplify these feelings, so we have decided to engage the news of reality. That is, the news based on what we see with our eyes (the streets are clear) and what we hear from others. (I call my loved ones in different areas, and they reassure me about their wellbeing, their family, and their neighbourhood.)

Really, the news of reality is different.

And this is my wish to you: Keep your inner peace and mental safety. We will have a homeland tomorrow; we want to build Sudan.

Dr Mohja Khairallah (left) at an advocacy event.

A moving tradition of Sudan to offer free water to anyone; these clay jars on the streets ensure hospitality is offered, even to strangers.

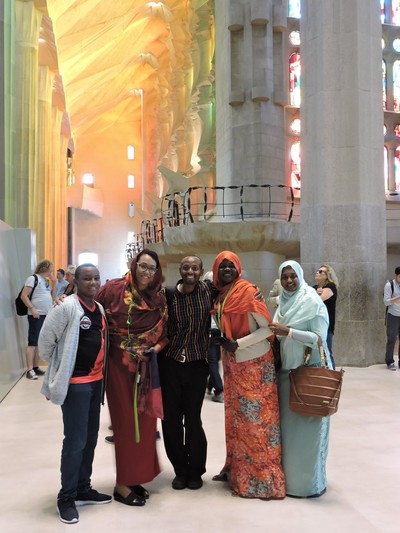

Photo taken in Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, where Dr Mohja Khairallah is second from the right. Dr Jack Turyahiko from Uganda stands in the center, with Dr Nahla Gafer in red next to her son Yousef.

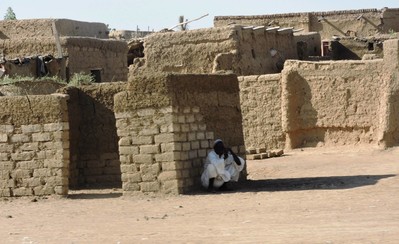

Photo taken of rural area, similar to where Dr Mohja Khairallah lives. Many people have left the city of Khartoum due to these recent events.

Lovely picture of Dr Nahla Gafer (center) and Dr Mohja Khairallah (right).

From the Sea to the Sahel: Palliative Care Lessons from Sudan and Mauritania

![]() Cairdeas

Cairdeas

![]() 11th April 2023

11th April 2023

This blog was written and submitted by Dr Nahla Gafer, a clinical oncologist at the Khartoum Oncology Hospital, Sudan. Today she shares about her recent visit to Mauritania and explains more about both Sudan and Mauritania.

Background

Dr Dave Fearon or "Dr Daveed" as he is called by Dr Ekhtelbenina Zein, director of the National Oncology Center (CNO), has been known as the first one to speak of and push for palliative care in Mauritania. This is our second invitation to Mauritania by Cairdeas Sahara. The first was in 2017 working with the volunteers at the community level and training general practitioners from different states (wilayat). Dr Dave Fearon has paved the way for this visit in order to impact the palliative care services at CNO. This time, we were three trainers from Sudan with more than 10 years of experience in palliative care for oncology patients.

Positive Aspects at the National Oncology Center

The administration and equipment exceed that of Sudan: the palliative care service has got a dedicated building, with dressing room, nurse office, counselling room, training area and offices for pharmacy, social worker, nutrition office and donating NGOs. All that in addition to the 8-bedded day care area. On the first day, we were met with the director of the hospital and the heads of the different departments. The director of the hospital struck us as amply knowledgeable and committed to providing palliative care to the patients in the center. Nouakchott Oncology Center, a 5 min walk from the Bureau of Palliative Services, provides high level radiotherapy treatments (3DRT, VAT and IMRT) as well as surgery (especially endoscopic), interventional radiology and targeted therapy.

Cultural Similarities

Across four countries in between (Sahel countries), and amongst the eleven neighboring countries for both, no two are so similar as Sudan and Mauritania in culture, nature, and landscape. With dress, for example, the thoub distinctive to married Sudanese ladies is almost the same malhafa, dressed by all Mauritanian ladies, though fixed in a different manner. Mauritania on the Atlantic Ocean is a bridge between North Africa and the Sub-Saharan Africa, as is Sudan facing the Rea Sea on the extreme east of the continent. Similar attire, similar traditions, similar gender roles, and almost similar beauty standards. Yet to reach such a country we had to travel northeast, leave Africa to Asia (Istanbul, Turkey) and then back southwest to reach Mauritania.

The South-South Interaction

Apart from the 12 interactive sessions given (for some candidates it was the first training they attend in palliative care), these were the highlights of the visit:

- Fostering a holistic responsibility for the patient by each of the team members

- Instilling the values of patient comes first, patient autonomy and patients’ rights, especially with the issue of families refusing the patient be told the diagnosis

- Working as a team and supporting each other

- Directing the financial aid according to socio-economic status

- Addressing spiritual issues (with rephrased questions in Arabic), which were previously ignored for two reasons: lack of insight by the patient, questions not adapted to Islam

- Implementing a summarized and simplified comprehensive four pages for PC clerking in Arabic (understood by the majority of the team members) compared to the French version which was 17 pages and with less than 50% of the team members able to write in French.

Future Plans

Unfortunately, the taboo surrounding cancer in Mauritania is so great that even asking about the symptoms is a problem. We, as a visiting team would like to co-ordinate further training of the treating physicians about breaking bad news, as well as an annual visit to improve the services – as mentioned by Dr Ekhtelbenina Zein, things can change step by step. Speaking more openly about cancer, we would like to help direct efforts for the early detection and screening, thus making use of the full services offered at CNO.

This two-week training period has opened the eyes of the staff to a lot of improvements that can be made. It is with such keen administration and caring personnel that positive changes are expected.

For us, as a visiting team, we have a lot to carry back to Sudan: this model of a stand-alone day care service; my colleague nurse who learnt how to prepare sessions and execute them in a conductive manner, and myself learning from the different aspects of care, especially becoming more proficient in convincing the families about patient’s right to know. It was great for them to attend the sessions conducted by Dr Mohja given in classical Arabic, while she made a second attempt to learn the Hassania dialect.

Many thanks to Cairdeas Sahara for making such a visit possible, with gratitude to Dr Dave Fearon and to the Mauritanian people.

Dr Benina Zein (in the center) handing Dr Mohamed Eleyatt (head of the PC team) the certificate after the 2 weeks training, together with the visiting team from Sudan - Sr Mahasin Ibrahim, Dr Nahla Gafer, and Dr Mohja Marhoom.

Oncologist Dr Ahmedou Tolba in front of a Halcyon Machine, with Sr Mahasin and Dr Nahla.

A photo out of the ward, with Dr Nahla Gafer pictured just in front of the sunset.

The doctors, nurses, social workers and nutritionists who attended the training together with the Director of CNO, at the Bureau of Palliative Services.

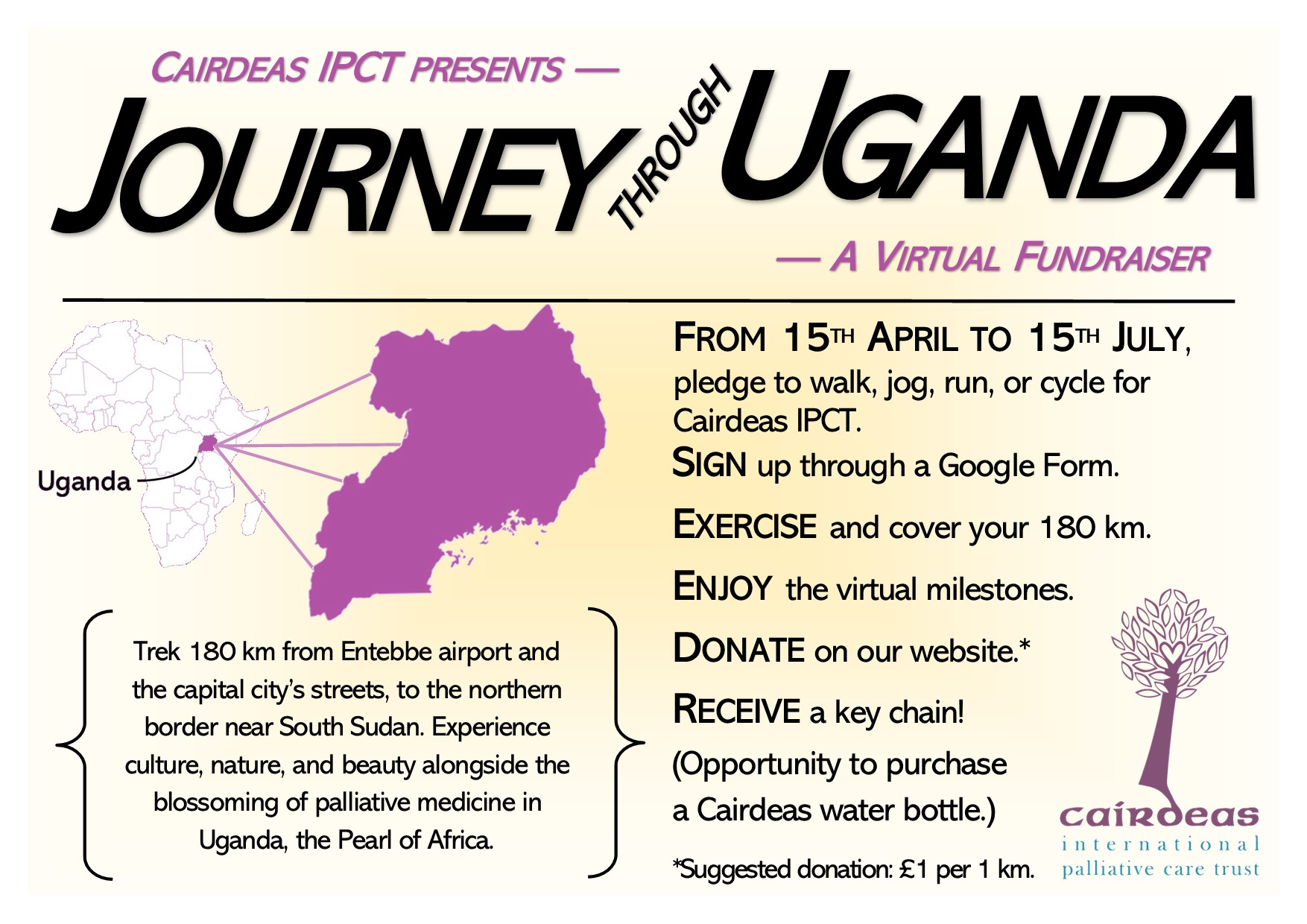

Journey through Uganda: Coming soon to you!

![]() Hannah Ikong

Hannah Ikong

![]() 27th March 2023

27th March 2023

Cairdeas is pleased to work with several partnering organisations, across many continents. One long-standing country that Cairdeas has served in is Uganda, called “the Pearl of Africa.” Uganda is also the home to many of our partners, like Palliative care Education and Research Consortium (PcERC) and Peace Hospice Adjumani (PEACHOA).

We welcome you to join us for a Journey through Uganda to explore its culture, context of palliative medicine and its development, as well as the natural beauty of this country. We’ll hold our virtual fundraiser of 180 km during the three months’ period of 15th April to 15th July. (This means, for those not living on the equator, you’ll be able to exercise while the weather is warm!)

During the 180 km covered, we’ll go through twelve different milestones of 15 km each where we will showcase the journey through Uganda in blogs, pictures, and videos.

- Join us for some insider looks into the travel, people, and history of Uganda.

- You will find recipes for some delicious Ugandan eats to replenish you after the exercise.

- And you will hear from those working in palliative medicine all across Uganda.

- Must also add a special note for avid birders! The natural beauty of the country will also be shared by a “Bird of the Day” which has been spotted and captured by our own Dr Mhoira Leng.

The timeline for these twelve different milestones are quite flexible: you may chose to complete each 15 km each day or over a week’s time period. Your journey and visit to each milestone on the trip will be completed on the honour system.

We would like to share a bit of the journey with you and engage electronically (email, WhatsApp) as well as send you an animal key chain from Uganda once you have completed the trip. Cairdeas branded water bottles are also available in limited quanities, to be purchased by the highest donations by the end of the fundraiser.

Your participation in the “Journey through Uganda” has only two parts! One is that, for the fundraiser, we ask that you submit your donation on our secure website or through our Just Giving page. Then, you can simply go through each milestone as you cover the distance by walking, running, jogging or cycling.

We are sure you’ll enjoy your time with us in #BuildingaWorldthatCares.

Interested? Fill in the Google Form to register and we can follow up with more information.

Brilliant cardio opportunities in the hilly Kampala, the capital city of Uganda.

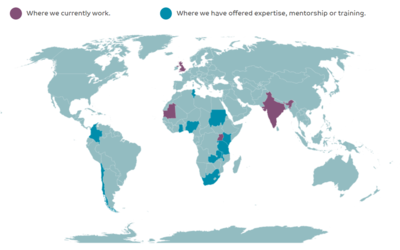

Cairdeas operates around the globe! We are pleased to work in Uganda too, marked in purple near the centre of Africa.

Join us in walking, jogging, running, or cycling. Wishing you open roads and clear skies, like pictured here in Kampala, Uganda.

A sneak preview of an agile avian species: the Grey Headed Kingfisher.

For those who are engaging in the fundraiser, we will bring you something from Uganda, like elephant or animal key chains!