Left Behind In Pain: WHO Report, June 2023

![]() Hannah Ikong

Hannah Ikong

![]() 10th July 2023

10th July 2023

Imagine trying to live with severe unrelieved pain caused by an illness such as cancer. The pain is overwhelming…. affecting your mood, your sleep, your ability to do the simplest task, and your relationships. The only painkiller you can find or afford is paracetamol which can’t relieve the severe pain. You feel an increasing sense of despair…how can you live with this suffering?

This is the reality for many millions of people across the world and an issue that Cairdeas and our partners see and seeks to address daily.

In the middle of June, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a new report that speaks to this reality. “Left behind in pain: extent and causes of global variations in access to morphine for medical use and actions to improve safe access.”

Dr Yukiko Nakatani, the Assistant Director-General of Medicine and Health Products in WHO introduces the growing crisis as “the persistent lack of access to morphine for medical use, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.” Nakatani continues, “This report underscores the fact that morphine is an essential medicine and a gold standard for pain relief that has been included in the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines since 1977” (p. 7).

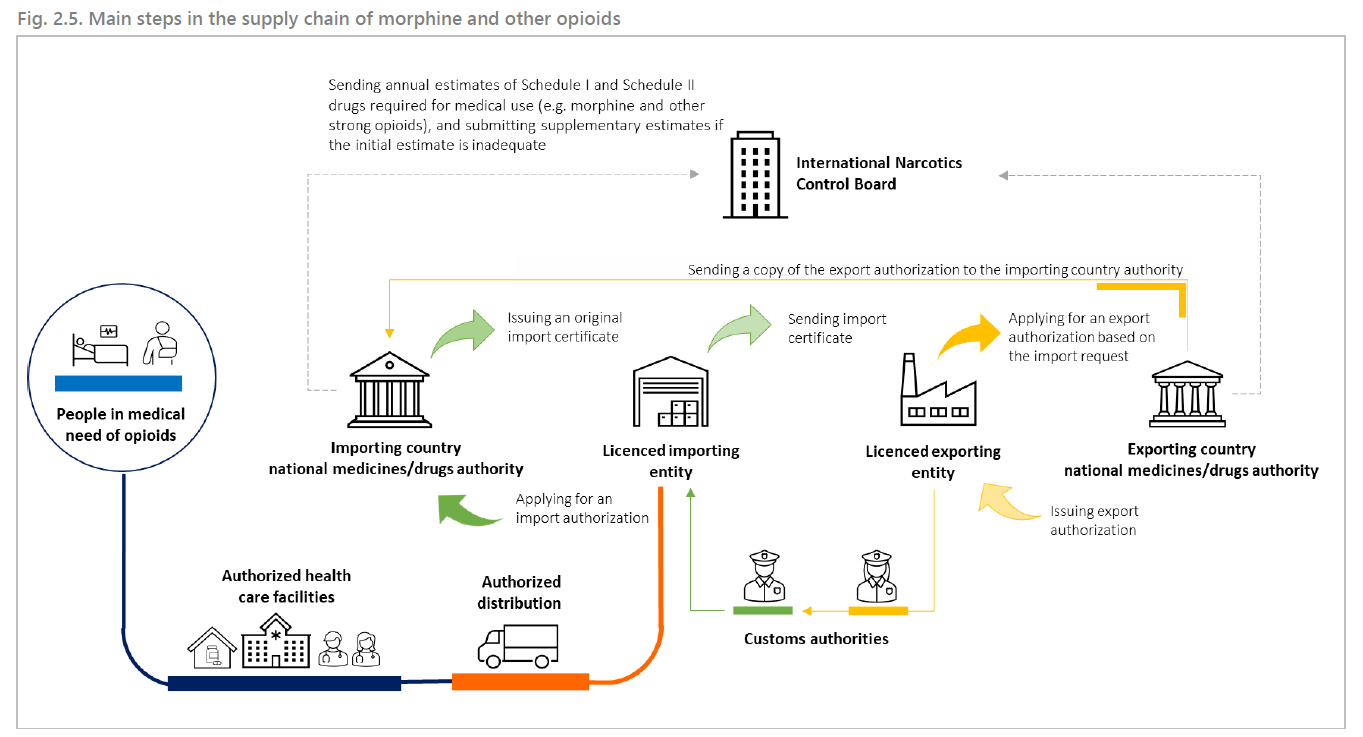

The barriers of accessible and safe morphine use are many. “Despite its importance, consistent and safe access to morphine is hampered by a range of factors, including a lack of coordination along the supply chain, inadequate physical, financial and skilled human resources, weak governance, and misconceptions about pain and opioids” (p. 7).

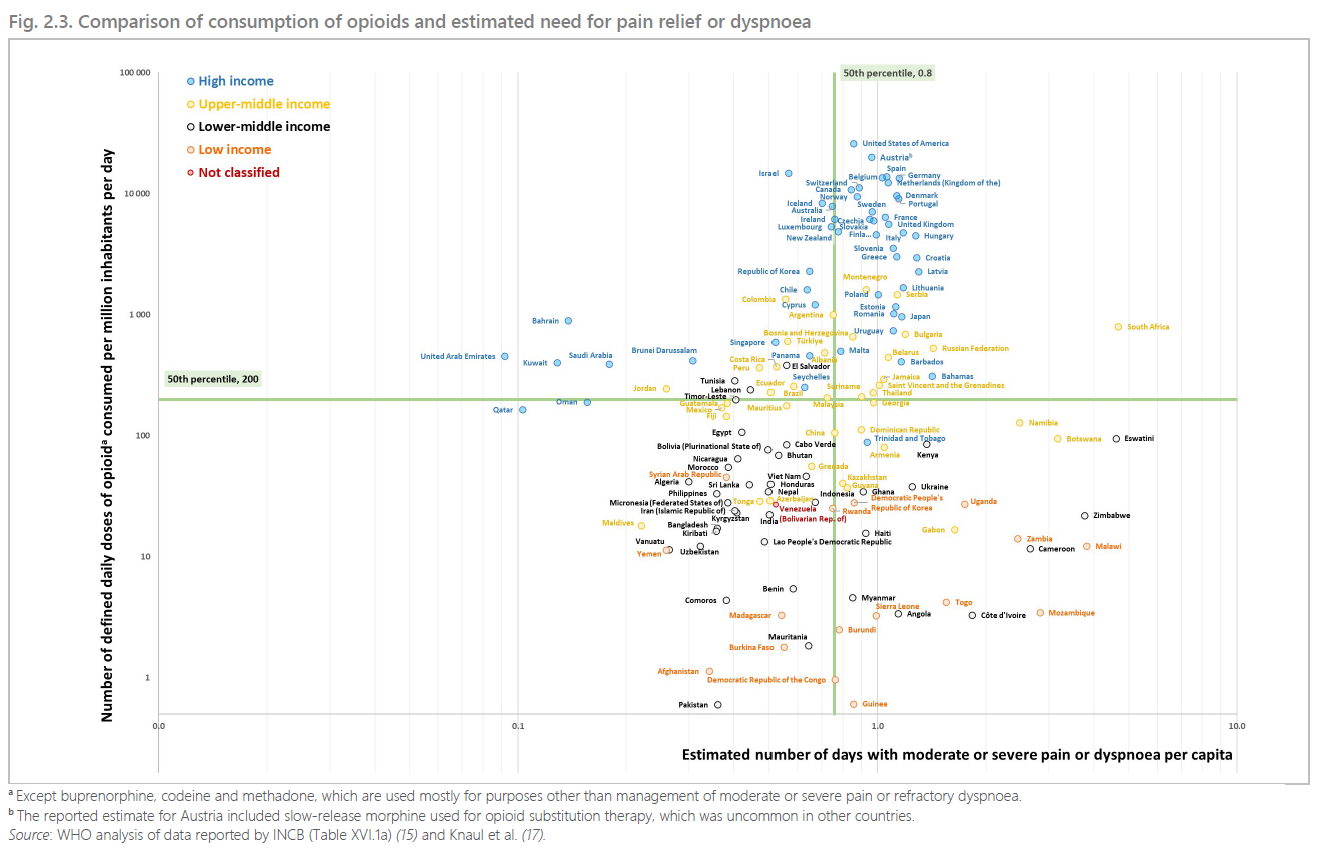

The report shows continued unequal and inadequate access to morphine: “more than 95% of all the opioids (in morphine equivalent doses) were distributed to high-income countries, with only 0.03% being distributed to low-income countries” (p. 14).

Due to inconsistency in the availability of morphine, half of surveyed lower-income countries reported that at least 80% of their patients could not receive morphine when needed (p. 22). These disparities play a toll, with estimates that half of the deaths worldwide include serious health-related suffering (p. 14).

We encourage you to download and read the WHO report here for the full details. Meanwhile we will highlight three areas of action recommended to improve morphine access below in light of our international work and partnerships in palliative care.

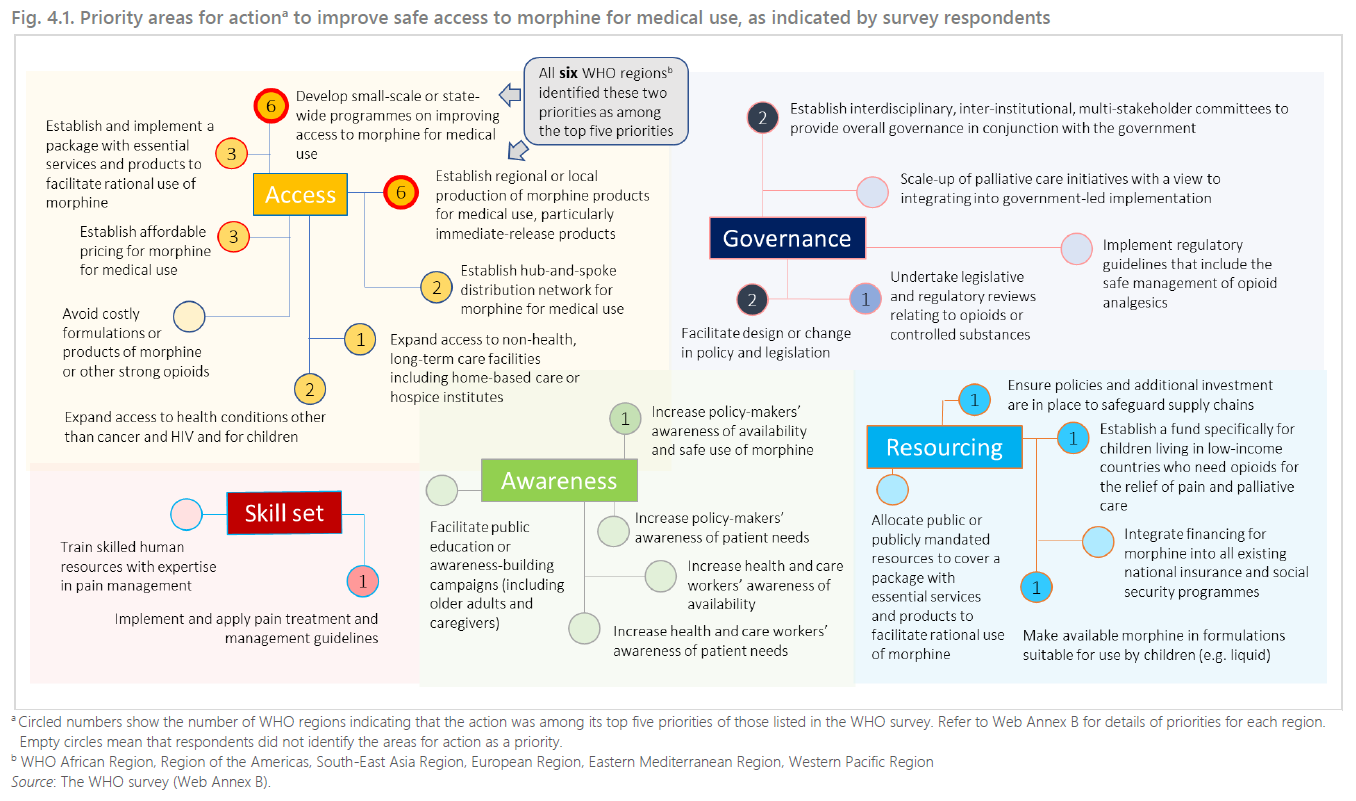

Recommendation #1: Policy work and government structures.

Advocacy work such as raising awareness about unmanaged pain and suffering as well as demystifying morphine and addressing fears among governmental leaders and health care leaders is foundational to morphine access. Such policy work can begin in regional areas, especially after a country has agreed to include palliative care but may not be able to implement it.

We have seen this before in different regions of Uganda, where we have been privileged to meet and share our needs assessment observations with the District Health Official (DHO) of Obongi district. Our reports to him regarding palliative care needs of refugees and hosts in their areas has gained the district’s attention and prompted their support of the work of our partners.

Or, in the hospital setting, advocacy involves the outlining the need for trained professionals and allocation of staff to either create or partner with a palliative care unit. Staffing support and training opportunities have come through two of the national hospitals in Kampala, Uganda.

Recommendation #2: Training of healthcare workers in morphine use.

Hand-in-hand with advocacy is the building of capacity for healthcare workers to safely prescribe, administer, and store morphine. This second recommendation may capture our most active part the Cairdeas IPCT international partnerships.

From the recent two-week training in Mauritania through colleagues in Sudan, to our professional diploma programme in the Gaza Strip in palliative care and pain management, to the revolving cadres of medical students and healthcare trainings in Uganda, palliative care education is foundational in all of our international work. Knowledge is key whether is transferred through training postgraduate doctors, providing clinical observation to palliative care nurses, or simply coming alongside the patient and caregivers in understanding pain management.

The WHO report agrees: “It is important to note that any efforts to improve the availability of morphine products must be accompanied by a health workforce that is well-trained in the use of opioids for medical purposes through professional education. Without it, increased product availability cannot translate into safe and effective pain relief for patients, and can cause wastage.” (p. 7)

Recommendation #3: Establishing systems and local production for morphine.

We are highlighting a third, from the many, recommendations of establishing reliable systems for morphine access and to include local production of morphine. Establishing hub-and-spoke distribution networks was prioritised for the WHO region in Africa through their recent survey, with other regions such as in the Western Pacific, adding affordable pricing and expanding access to different facilities.

While Cairdeas IPCT and our partners are not directly establishing systems or areas for morphine manufacture and distribution, it is through our collaborative advocacy, research, and education and training that will build systems. And these systems through palliative care can be transformational.

As Dr Mhoira Leng has shared in the recent conference for ICMDA in Arusha, Tanzania, palliative care is values-based care: “promoting dignity, relieving suffering, demonstrating compassion, fighting for justice.” From transforming the individual lives, to the medical practise, to the institutional systems and society as a whole, with the knowledge and application of palliative care comes transformative power.

See below for a list of recommended actions from the surveys collected by WHO for their June 2023 report.

Cite:

Left behind in pain: extent and causes of global variations in access to morphine for medical use and actions to improve safe access. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

World Health Organization Report sharing the on the current accessibility of morphine around the world.

Dr Yukiko Nakatani, the Assistant Director-General of Medicine and Health Products in WHO.

A quote from a patient who benefited from pain management and other holistic care. "You gave me hope, you gave me pain control, you gave me love ... make sure everyone in Uganda has this care."

Highlighting fellow colleagues in advocacy: senior nurse Florence Nalutaaya from PcERC (left) stands alongside PcERC Board Member Prof Julia Downing (right).

The group leader (left) during a Nurses training giving account for the team’s list of fears and side effects of morphine to PcERC Clinical Leader Liz Nabirye (right).

A snapshot from a virtual teaching session in Gaza, led by Drs Khamis Elessi and Mhoira Leng.

The Needs Assessment team of researchers from Cairdeas IPCT, PcERC and Peace Hospice visit the District Health Official of Obongi District.

An illustration of the transformative power of palliative care: metamorphosis.

Palliative Care Training for Health Professionals in Kiruddu Hospital

![]() Hannah Ikong

Hannah Ikong

![]() 5th July 2023

5th July 2023

The palliative care training at Kiruddu National Referral Hospital in Kampala, Uganda, was for only two days yet its outcomes are limitless.

One participant, a social worker named Musa, attended the training in June told me, “I have been seeing these people around, the ones of palliative care, but now I know what they do. I am going to work with them.”

Musa is one of the 26 professionals who has completed the training and now is one of the mentees on the ongoing mentorship with the Palliative care Education and Research Consortium (PcERC).

The PcERC team delivered this jam-packed two-day training in two groups; the first given over September 15-16, 2022, and the second on June 29-30, 2023.

The trainees included nurses, pharmacists, and social workers who are employees of Kiruddu Hospital. Sessions covered the basics of palliative care, with a holistic approach and communication skills training, and how to integrate them in their own profession and setting.

Daphine, a hospital pharmacist, had several takeaways from the training, as she plans to spend more time with patients and their families. In particular, she wants to practice her new-found communication skills to explain their prescription, identify and address fears, and be sure to educate them on possible side effects and how to manage symptoms.

Daphine and other participants were able to demonstrate their skills through role plays in the training, groupwork, and group presentations with instructor feedback.

They were also given laminated copies of the Pain and Symptom management protocols, to keep at their respective hospital stations for reference.

The PcERC team received evaluation feedback from the training, with most participants requesting for more time for the palliative care training and about a third specifying that they wanted ongoing training updates on palliative care.

Reported key takeaways were on pain assessment, pain management, communication skills (including breaking bad news) and end of life care.

The hospital administrator, Mr Elisa Mugisha, opened the second group of training in June and spoke on the need for palliative care. “Integrating this kind of care which has been missing is going to be a great asset,” he told the nurses, pharmacists, and social workers.

“In the medical field, it is important to modify the curriculum and to keep improving the curriculum. I would like to encourage the people who are attending to implement this programme and to be sure to let the team know if you have any problems. We commit to support you.”

After his address, he mentioned to the PcERC team that, “You can even start training every month, and train another group to make critical mass of people in July!”

The support and welcome for palliative care in an integrated Ugandan Ministry of Health hospital cannot be any better than that.

These trainings have been supported by Cairdeas IPCT and we are pleased for the reception from Kiruddu Hospital administration and healthcare professionals.

Many thanks to all partners for the trainings and ongoing mentorship.

Group work during the training: Palliative care nurse Cathy Magoola (left, in green) leads her team in outlining morphine myths and fears.

The first group of palliative care training, completed September 15-16, 2022 in Kiruddu Hospital.

PcERC Clinical Lead Liz Nabirye speaks on grief and bereavement to the healthcare professionals.

Role plays and skits are performed on breaking bad news (communication skills).

The second group of training is completed on June 29-30, 2023.

Senior nurse Florence Nalutaaya who has helped coordinate this training also reviews the pre- and post-tests and competencies.

Making it Count: Journey through Uganda in June

![]() Hannah Ikong

Hannah Ikong

![]() 16th June 2023

16th June 2023

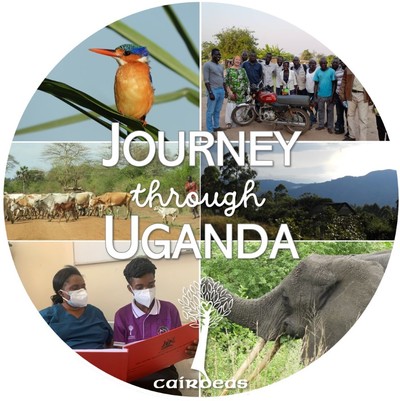

How can we promote accessible and compassionate palliative care in Uganda?

Through a fundraiser walk? These days, counting each kilometre—or mile or step—can seem like a drudge of numerical exercise. Akin to a sitting room workout, we wonder on the point or reasoning behind so many push-ups every day.

I have participated in walks and other fundraisers before, but this year’s Journey through Uganda is more than the numbers completed. Actually, the journey is as much as a learning process on palliative care development as it is a reflection and a prayer.

You may have already started the milestone journey on our website. You’ll find that a cornerstone of the work in Uganda is education: training those who are working in health care and building capacity in our partner’s staff. Three of the Cairdeas scholars live in Uganda, with two advancing in social work while another completes studies in nursing.

We conducted a new interview with one scholar, Philip Amol Kuol, to hear his experience as a South Sudanese refugee, social worker, translator, and community health advocate. Philip recently told us, “Most of the patients are dying because of lack of good care to them. Because the more they realise that you are almost giving up on them, they feel like they should die … but if you have committed yourself to give good care to the person, the person will feel more that people still love them in the world.”

He shares more about the dignity and restored life given by access to quality palliative care below.

A recent pilot research conducted in the area where Philip Amol lives brings new perspective to the lived experiences of those with chronic illness. As we look through the Photovoice methods, from pictures taken and critical dialogue recorded, the reflection on Journey through Uganda continues.

In May, another scholar named Godfrey Oziti from Peace Hospice discussed his passion for palliative care with me. He defined his work as “a kind of care that gives the patient’s life back and is enjoying life again” and added: “I like to transform the patient so they are not just counting down the days.”

To cease the counting down of days to refocus on life again for a patient, I muse, as I think of how I count the kilometres for Journey through Uganda. Both involve numbers, yet I find joy in my counting exercise of this first-ever Cairdeas IPCT walk.

While I exercise and support the work of Cairdeas’ partners in Uganda, a chronically ill patient has just been treated and cared for with dignity and respect. As we build up the fundraiser more this June, more patients and their families find hope amid severe health-related suffering as trained health care professionals address physical, psychological, emotional, and spiritual concerns.

Our support during the Journey through Uganda funds those like Liz Nabirye, a Clinical Officer and Lead in the Palliative care Education and Research Consortium (PcERC). She not only offers consultations at no-cost to hospitalised patients but also trains dozens of medical students in palliative care.

I had the honour of attending a training with Liz Nabirye last week. When the question was asked on how to motivate a chronically ill patient to choose a healthy lifestyle and attend counselling, the rest of us were quiet and puzzled. Liz said, “There is a need to understand the circumstances which contribute to this person’s situation and identify what they think as a patient need to achieve. For example, there is need to be patient-centred and holistic in nature, which will definitely require multi-disciplinary support.”

The knowledge, skills, care, and approach being held by our partners Peace Hospice and PcERC have been spreading to their professional colleagues and medical students. Holistic palliative care is more accessible than ever before, and all at Cairdeas IPCT are pleased to be working with those in Uganda.

What an impact and how much value is being created for compassionate palliative care! Join us and register for the Journey through Uganda fundraiser this June.

Registration is open: from 15th April to 15th July this summer!

A leafy hillside road in Kampala, Uganda: a great place for reflection.

Toko Friday Santiago (left) stands with Philip Amol Kuol (middle) and Dr Mhoira Leng.

Godfrey Oziti during training of village health teams (VHTs).

Dr Mhoira Leng leads an initial analysis on Photovoice pilot research with (left to right) Simon Maku, Toko Friday Santiago, Immaculate Atim, and Vicky Opia.

Liz Nabirye (right) walks alongside Jennie Twesige (left) to Mulago Hospital, Kampala.

Engage in the journey with us; after registering you can join our WhatsApp group!