Meet Cathy Namuto Magoola: Cairdeas Scholar

![]() Hannah Ikong

Hannah Ikong

![]() 22nd March 2024

22nd March 2024

Meet Cathy Namuto Magoola, the newest Cairdeas Scholar! Last month, Cathy began a one-year Advanced Diploma in Palliative Care programme with the Mulago School of Nursing and Midwifery in Kampala, Uganda. We are pleased to partner in Cathy’s nursing education and appreciate her role with PcERC at their unit in Kiruddu National Referral Hospital (KNRH).

We first met Cathy nearly two years ago, in April 2022, as a nurse who was assigned by KNRH to work with the palliative care unit (PcERC, that is, Palliative care Education and Research Consortium). As a government nurse, Cathy did not have much prior experience in palliative care but was interested in the field and eager to learn. With the supervision of Sr. Nurse Florence Nalutaaya in PcERC, she soon was providing palliative care to the patients and families at the hospital.

I have interacted with Cathy on many occasions, and from the beginning, she has always had a kind heart and listening ear. When we sat down for the interview (as the newest Cairdeas Scholar), midway Cathy quipped, “I’m talking too much!” Yet it is good to hear from Cathy and understand her approach to palliative care, with almost two years of on-the-job training with PcERC and new studies in her Advanced Diploma.

“My mentors are nurse Florence and nurse Berna,” Cathy told me, “And they have not only been my mentors but my models in palliative care. I’ve learnt so much from them. Once, we had a patient who was really struggling on Level 5 in Kiruddu Hospital. His caregiver had abandoned him, and he had no one to help him get anything to eat. He was on oxygen, laying in bed, and too weak to go and do anything.

She continued, “Nurse Berna found him one morning, trying to negotiate with another patient’s caregiver to help him eat, but that other carer was not taking the time to help! Berna stopped immediately and took time to feed the patient herself. Once he was strong enough to eat on his own, Berna worked with the hospital staff and with PcERC’s Comfort Fund to ensure the patient received food in a timely manner. He has already passed away, but he was very happy with Berna and appreciative of our palliative care team. I learned then that I have to create time for our patients.”

Her time now is stretched between working on the ward and attending classes for her Advanced Diploma in Palliative Care. “We attend class from Monday to Friday, and after the 5th of April, I will be going on a clinical placement for a month” Cathy told me. “Once we come back in May, there will be more classes and end of semester exams. I have been learning such amazing and new aspects of palliative care in class, from our course material to the experiences shared by my tutor and fellow students. These all help me be prepared for what is ahead of me.”

What are the next steps for Cathy? In the immediate future, she is in an ethical issues course unit and is learning about will writing. “They are teaching us the foundation of palliative care, and we are each also preparing for a research project. I’ve identified my research topic to study on as ‘The Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices of Healthcare Workers in KNRH.’ I was very much interested in end of life care and researching that at my hospital, but they said that was done recently, so I am looking at the healthcare workers instead.”

“I have been very motivated to start this programme so I can be certified in prescribing [pain medication such as morphine]. Often I find one of our patients in pain and yet currently, in my level of nursing, I cannot prescribe anything for them. I have to go and find a doctor to write the prescription – and they are not always on the ward – while the patient waits in pain. With this Advanced Diploma in Palliative Care, I will be certified to prescribe, and be among some of the only nurse prescribers in Uganda.”

Cathy likewise hopes to continue her education in palliative care. “In the next 10 years, I would like to do my bachelor’s in nursing. One day I hope to go into management or tutorship, so I can teach fellow nurses.” When I asked her what she would like to teach, when she is a senior nurse, she quickly vouched for palliative care. “I want to stay in palliative care; the more that I work in this field, the more experience I get, the more I like it actually.”

“Many think that palliative care is for the dying,” Cathy told me. “But no, palliative care is aimed at improving the quality of life for the patient with life-limiting conditions. It needs to start from time of diagnosis; they shouldn’t wait to call in our palliative care unit when the patient is actively dying.”

She’s communicated about palliative care recently to a surgeon who wasn’t yet ready to refer a patient with stomach cancer to palliative care. (The surgeon compiled, sending the patient and the family to the unit for support as they navigate cancer treatment.) She has been advocating for palliative care in KNRH and even in the other national referral hospital of Mulago. Cathy has well deserved her scholarship support from Cairdeas IPCT, which has supplemented her partial scholarship from the Palliative Care Association of Uganda (PCAU).

We are excited to see what is ahead for Cathy Namuto Magoola and with her work in palliative care, the Ugandan government hospitals will be a better place.

Meet Cathy Namuto Magoola; a government nurse stationed with the PcERC unit in Kiruddu National Referral Hospital.

Sr Nurse Florence Nalutaaya (far left) from PcERC demonstrates the correct morphine dosage to Cathy Namuto Magoola (second from left), he patient and caregiver.

It's Hat's On 4 Children's Palliative Care time with #ICPCN - this was last October with nurses Bernadette Basemera (left) and Cathy Namuto Magoola (right).

Cathy Namuto Magoola (far left, in green) participates during a group activity during a Healthcare Worker's Palliative Care training by PcERC.

Sunshine in a Time of War: Palliative care and cancer care in Sudan

![]() Cairdeas

Cairdeas

![]() 12th March 2024

12th March 2024

This blog was submitted by Dr Nahla Gafer, our Cairdeas IPCT lead for palliative care in Sudan.

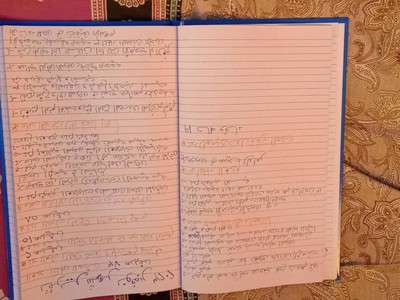

Almost a year ago, all our worries at the palliative care unit were how to establish home care in a systematic way as to be available to all patients nearing the last phase of their lives. The palliative care unit was formed of volunteers working at the main oncology hospital in the country. The unit had (by then) completed 13 years since its initiation and had established an outpatient clinic with > 50 patients coming twice a week, in addition to the inpatients and the home care visits.

No one had expected a war, and our world was turned upside down. I was worried about my colleagues, family, and friends but I was more worried about my patients. GA is a 35-year-old lady with a devastating vulval tumor. She cannot sit straight; in public transport she needs to lie on her side. Her pain was controlled by 6 tablets of 15 mg of morphine every 4 hours. We reached a point of convincing her to try a mild chemotherapeutic agent, after her last chemotherapy treatment, which was 2 years ago, and during which she had severe side effects, and was very reluctant to go back to chemotherapy. At last, we had a promise from her to try this mild chemotherapy after Eid. Then the war came.

AK had multiple ulcers from his squamous cell carcinoma, now running havoc all over his face, neck, back, limbs, etc. It did not help at all that he was albino, and my role was not only to find alternative ways to reduce the disfiguring masses and control the oozing and pain, but also to support him, and help tackle his psychological and social issues. OA is a lovely girl of 12, being informed by her attending physician, that nothing more can be done for her, her mother came to the unit seeking support. Building up her general condition and managing her pain, she was back on tract on active treatment with good response. She went on to speak on breast cancer month, to schoolgirls her age saying that the disease is a test to her faith, and that endurance brings one nearer to God. She thanked her family and treating physicians and really showed how one can really be so strong in spirit inside a weak body. For some months after the war, we lost contact.

Those are a few of almost 1,000 patients we were serving when the war broke out. The first priorities once the war started was to go to a safe area and ensure you have food. There are certain things that are already lost: your property, house, furniture, car, office, whatever you previously had, and your source of income. All forms of normal life, including work, stopped; the internet was so weak that a message sometimes takes a week to get through, and our local internet banking was not functioning. After this was sorted out, we were still so worried about our patients and about our colleagues.

The international community stood by us, and through donations, we were able to mobilise our colleagues and their family members outside of the hot conflict areas. A plan was set with Cairdeas International Palliative Care Trust (Cairdeas IPCT) and SANAD The Home Hospice Organization of Lebanon, to support the team members, some of whom had remained in war zone areas for 3 months. We then created “Sunshine in a Time of War,” a project by Cairdeas IPCT and SANAD The Home Hospice Organization of Lebanon aimed at supporting the palliative care unit. Even before the project was implemented, just the idea that you matter to someone and that someone is ready to help, gave the team members a lot of strength.

Sunshine in a Time of War holistically supported the palliative care team in Sudan. Psychological support to the members of our palliative care unit was very important, and we needed to provide debriefing and psychological first aid (PFA) training. This resulted in multiple contacts with team members from those from SANAD The Home Hospice Organization of Lebanon, who assessed how they were doing, providing debriefing and referral to local services for psychological support, as well as offered training through a video series posted on YouTube. Financial support to the team was also essential, which included providing for their phone and internet assess while working as well as supporting their salaries, organised by Cairdeas IPCT. [Many thanks to the generous supporters and friends of Cairdeas IPCT, who played a large role in supporting our palliative care colleagues in Sudan!]

During the Sunshine in a Time of War project, we faced several challenges. For example, no one could reach the hospital, where we had the computer with all patients’ data, their contacts and their family members contacts. We had to find another way to reach the patients as soon as possible and as many as possible. We collected all numbers we previously had in our smart phones, especially from the nurse who was had the habit of calling patients the second day following on their pain medications. The team members started reaching out to patients through telephone calls, WhatsApp and messenger text and voice messages. The main purpose was to check on their security, advise them with practical issues, as well as check on their disease and what to do about it.

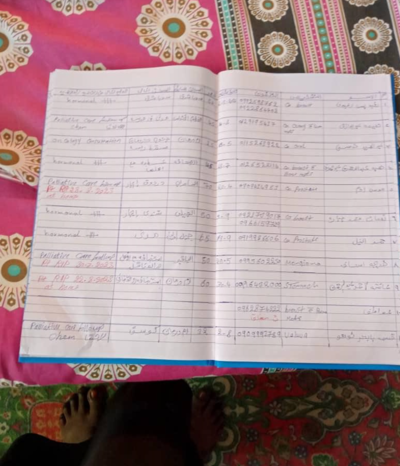

More than 400 patients were reached, all documented nicely in ledgers kept in a make-shift office, in a remote city, in the north. We made sure to record the diagnosis, time of diagnosis, stage, previous anticancer treatment received, current complaints and current situation. The 10 years of work at the palliative care unit made our team very competent in palliative care and in oncology, especially in managing all problems: physical, psychological, social, and spiritual. At times, when there was need for further consultation, myself and another two doctors were reachable by WhatsApp. The palliative care unit were also able to contact SANAD The Home Hospice Organization of Lebanon, for psychological support for themselves, the patients and their families. While the palliative care unit no longer existed as a physical place, it turned into a virtual network connecting 400 patients with 8 Sudanese staff and 4 Lebanese staff, supported by Cairdeas IPCT and SANAD The Home Hospice Organization of Lebanon.

The amount of support we could give to the patients remotely is amazing. Even end-of-life care was conducted remotely. KA had liver metastasis that affected his liver function, but the family was not aware how terminal he was. A series of calls to the family was very helpful in exploring his current complaints, checking the signs of eminent death (examining the mouth ulcers, other complaints, etc.), explaining what was beneficial and what is not through family meetings conducted with the family members in a separate room, and the camera directed to the person who was speaking. Yes, it is possible to conduct virtual family meetings as well as virtually assessing symptoms, discussing with the patient, directing, and even prescribing medications. (Prescriptions were written, photographed, sent by WhatsApp to the family.)

We received several messages of thanks and gratitude from the patients and their family members. Yes, we helped them, they needed us, but also, we needed to preserve the work that we had started; we needed to help our patients. It is part of who we are. This way we are really healing, caring and humane health professionals.

Record-keeping is now pen and paper, WhatsApp photos and chats when possible.

A picture taken during a home visit in Sudan, although it has been rare to see patients in person.

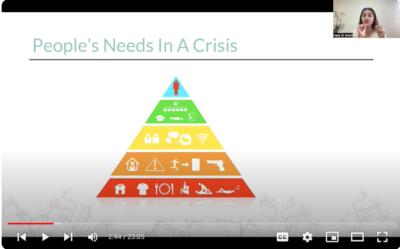

Training for Psychological First Aid was completed virtually through a video series for the palliative care unit, from SANAD.

Notes for patients are collected and photographed to share with the doctors, like Dr Nahla Gafer. This is a summary of patients seen by Nurse Mahasin in November 2023.

The palliative care unit continues to care for patients and families, even during this time of war.

‘Inspire, Empower, Influence and Transform:’ Compassionate Leadership Fellowship update

![]() Hannah Ikong

Hannah Ikong

![]() 11th March 2024

11th March 2024

As palliative care providers, leadership development is key to building our teams and expanding our reach in healthcare provision. Even more so, compassionate leadership development touches on the goals of palliative care to reduce suffering, promote dignity, fight for justice and improve quality of life.

Compassion is a paradigm we speak of in relation to our work with those needing palliative care but what about the focus on how we lead, how our organisations are run, and how we bring forward the next generation of colleagues. Thus our focus is on holistic personal transformation in order to transform our settings and increase our influence.

The Compassionate Leadership Fellowship (CLF) has been made possible by partners Believers Church Medical College Hospital (BCMCH), Cairdeas International Palliative Care Trust (Cairdeas IPCT), Global Health Academy, University of Edinburgh (UoE), the Indian Association of Palliative Care (IAPC), and RMD Trust. We are also grateful for previous opportunities internationally for many involved including the LDI programme (thanks Frank Ferris) and innovative programmes in India and Uganda that helped shape our CLF.

In its structure, the CLF is taught using a blended learning modular format. Modules 1 and 3 are six days held in person at BCMCH in Thiruvalla, Kerala. These modules bookend Module 2 which has monthly online sessions. In addition to the taught sessions the CLF has a mentorship programme which is key to the transformational learning design. We are fortunate to have experienced mentors who attend all the training events as well as work on to one online. They have also committed to visiting each Fellow at their place of work.

February 18th of 2024 marked the official beginning of the CLF with an inauguration ceremony of music, prayers, and calls to compassionate care and leadership in the healthcare systems of India and beyond. We were proud to commence the first CLF cohort with 19 Fellows (16 from across India and 3 others from Rwanda, Kenya, and Nepal) and 13 Mentors, and great support from all partners involved.

The programme’s co-chairs, Prof Chitra Venkateswaran of BCMCH and Dr Mhoira Leng from Cairdeas IPCT, reminded us of the connection of previous leadership development programmes and our future to strengthen even more leaders in palliative care. We welcomed videos from our partners nationally and internationally with a warm reception from our hosts BCMCH.

The first in-person module (February 19-24, 2024) allowed us to explore the characteristics of leadership and understanding oneself as a leader. We are using the widely recognised Leadership Development Index which offers 5 exemplary characteristics for effective leadership. We explored these together including our personal integrity, how we inspire and enable others, how we effectively challenge and support change and how we do this within a compassionate supportive environment. There was plenty to reflect on and learn even for the ‘experts.’ Our Fellows used a creative approach to present “Who am I as a Leader,” helping us get to know each other but also establish our leadership strengths and areas for growth.

A core aspect of leadership development is self-awareness, so we utilised tools with expert facilitation and then added group work, activities, and self-refection to help deepen our understanding of ourselves and how this impacts others. For example, the Myers Briggs Type Indicator gives insight on how we re-energize, interpret the world around us, make decisions and order our world. The KELP tool explores our preferred learning style, and we will use these foundational tools during the whole CLF programme to support our fellows in teaching, leading teams, and negotiating with others more effectively.

Our time together in February 2024 culminated in a leadership development plan (LDP) which Fellows will finalise in sessions with their Mentor. In addition to planning for personal development, the Fellows are agreeing to plan leadership activities that follow the S.M.A.R.T.P.A. guidelines (i.e., Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, Time-bound, Person-responsible, and including Accountability.)

We look forward to the ongoing interactions and growing bond between each Mentor and Fellow, as they journey through transformational compassionate leadership development and as we together form a crucial community of practice. We now embark on monthly teaching session online covering topics such as strategic planning, team building and dynamics, organisational development, teaching, and research, supported by national and global experts.

Our fellows have shared feedback already, so early in the CLF programme. After the first in-person module together, fellows took turns to write and share the following:

“It was a wonderful, fantastic self-introspective workshop. Really enjoyed the way it was scheduled and conducted.”

“Here is a heart filled with gratitude to our Organizers and Mentors. Trust and fun filled new friendships. Experienced, learned and grew more than I ever expected. Here’s a changed me to Model the way, Inspire, Enable others, Challenge and Encourage the hearts.”

“Just wrapped up an amazing workshop. Great learnings and looking forward to more. Thank you all.”

“Thanks to Dr Chitra, Dr Mhoira, Dr Leejia and all those involved in careful planning and execution of 1st CLF ever. It was a great learning experience. My take home message is not to waste our energy on things we can’t change. Instead concentrate on what we can change … not to forget my mentors … all of you who will have a hand in a changed ME.”

As we look to the months ahead, there is transformational growth in our journey together from knowing who we are as a leader to becoming changemakers in compassionate care. The CLF is not in the numbers only of 19 fellows with 13 mentors, interlocking 6 countries in 2 in-person sessions, 10 online sessions, and over 190 mentorship meetings. Rather, there is boundless impact through this compassionate leadership development, in ourselves and for our teams and health systems, our patients and their families.

Quality palliative care for all is comes from the development of compassionate leaders, and now that we have begun, the sky is the limit.

Group photo of fellows and mentors in the CLF programme; in front centre sits Dr Mhoira Leng, Dr George Chandy of BCMCH, and Dr Chitra Venkateswaran.

Inauguration ceremony involved each partner representative lighting the flame at BCMCH.

Small group discussions were key during the CLF, as mentors sat with their fellows during the programme.

Classroom activities included individual and group presentations, role plays, and other activities to help visualise the taught concepts.

A lovely afternoon in on the Backwaters of Kerala, India brought sessions of Encourage the Heart, shared leadership journeys, and times to connect and grow as a group.

A tangible key takeaway; kitenge document folders were hand sewn and sent from Uganda; a daughter of one of the PcERC team members made excellent materials for the CLF programme.

We look forward to reuniting online, and our next CLF programme in February 2025!