Gaza Update: Holding Onto Humanity

![]() Cameron Don

Cameron Don

![]() 15th May 2025

15th May 2025

Our Medical Director, Dr Mhoira Leng, shares an update on the situation in Gaza. Sharing testimony from Cairdeas partners and graduates in Gaza on the bombing of hospitals, forced displacement and starvation, Dr Mhoira and our partners call upon all of us to keep telling of Gaza, and give practical advice on how to respond in solidarity.

What is closest to my heart at this time is Gaza and the people of Palestine as they face almost unbearable catastrophe and suffering. Just over a year ago, I was in Rafah and was an eye-witness to the unfolding genocide that has continued and deepened to levels which are hard to fathom. Genocide is a stark word, however this conclusion is not my own, but that of many experts in international law, human rights organisations and even many holocaust scholars.

Telling and hearing the truth of what is happening on the ground is extremely difficult with a total block on international journalists, a lack of transparency in many of the international news outlets and a fog of propaganda. Doctors have become conduits, directly verifying eyewitness information from trusted colleagues in Gaza. Life expectancy has dropped by 35 years as the numbers with horrific injuries rise daily. The total blockage of food, humanitarian aid and medical supplies which leads to no treatment for basic medical problems such as epilepsy, or high blood pressure and even less for cancer. Now we are seeing the horrific scenes of forced starvation stalk this tiny strip of land and the weakest being the most vulnerable; the young, the elderly, the sick.

Listen to Randa, a nurse and one of our Diploma graduates as she speaks of the bombing on the European Gaza Hospital.

'As a nurse at the European Gaza Hospital, I am trying to reach out and let the world know that the hospital is now out of service. Since yesterday, we have been relentlessly bombarded with missiles and shelling that has not ceased. This forced all patients, the injured, children, and every department in the hospital to flee — along with the medical staff. We left carrying only our bags and our tears, helpless and devastated. There is nothing we can do — the occupation spares no one: not the sick, not the staff, not the wounded, and not even children. We evacuated, but there are still patients in the ICU, along with nurses and doctors who chose to stay behind to care for those on ventilators. They could not be evacuated due to the lack of available ICU beds and life-support equipment in other hospitals. We have stared death in the face more than once, unsure each time whether we would survive the next strike or not.

Bearing witness to what is happening has taken me to many different places, countries and people; from churches, solidarity vigils, interfaith groups, to a wonderful conference in Malaysia with the Asia Pacific Hospice Network. I am part of the executive of PallCHASE (www.pallchase.org) and also the Scottish Palestine Health Partnership (www.scotpalhp.org and see the next conference flyer) through which we seek to build networks, and hope and plan for the day when we can start to rebuild but also commit to telling of Gaza and each and every day. (see the wonderful poem by Khawla Badwan, featured to the right)

Advocating for better access to care for people living with chronic disease has been a major part of our work. Imagine having no access to medications to control your heart problems or kidney disease or cancer? We worked hard with the WHO to try to ensure pain control was available for those injured in bombs and fires, for those with cancer, for those needing surgery. Sadly all our efforts have come up against the almost complete blockade of food and medical supplies and has led to NO oral morphine. I continue to work with colleagues all over the world not only for Gaza but also to ensure this has a much higher priority in any emergencies such as Ukraine, Myanmar and Sudan through a network for palliative care in humanitarian settings.

Let me share some reflections from our Gaza colleagues, ways you can be informed and also ways to be involved.

Our dear friends have moved from asking for our help to speaking of their exhaustion and endurance yet also a deep sense of abandonment from the international world.

"They say “a difficult night”?! As if during the day, flowers are showered upon us…As if the nights before were calm?! All our moments are harsh…All our moments are painful…From the break of day to the end of night…All our time is stained with blood, filled with body parts and corpses…There is no calmness here. We are dying every second. ��" Suha Sulima Shaatt

"My dear Mhoira asked me for some moving words about the situation in Gaza... I couldn't find anything in the dictionaries of Arabic, English, or any other language in the world that could describe what happened and is happening in Gaza. These are summarized to reflect the values of the modern world, proud of the values of justice, humanity, and dignity. We recently realized in Gaza that these words and terms are only valid for use by the powerful in this world. So let us be silent and not disturb any of the evils of the civilized Western world.’" Suha Sulima Shaatt

I speak with Dr Khamsi Elessi, our Cairdeas partner in Gaza, regularly. He has now been forcibly displaced along with his extended family 16 times, just imagine the upheaval! He spoke just after the terrible bombing of Ahli Christian Hospital to encourage healthcare colleagues in solidarity.

"After 17 months of this barbaric carnage against our people in Gaza strip, which has left more than 60000 deaths and more than 120000 injuries, still there is a major disaster that is always overlooked by the mainstream media which is the forced eviction of people from their houses, tents or shelters. Being evicted suddenly with your family under fire again and again feels like a relentless cycle of fear, despair, and exhaustion. Every time I think I’ve found some safety, it’s ripped away after a short while, leaving many Palestinians displaced, vulnerable, and struggling to hold onto hope. This constant fatal uncertainty wears us all down, making survival feel like an endless battle with no safe refuge in sight.

To doctors and healthcare workers in Scotland who stand in solidarity and want to help Palestinians in Gaza strip, I say, your compassion and support mean more than words can express. In times of crisis, knowing that people across the world care and take action brings strength to us in Palestinian hospitals and to the hundreds of thousands facing unprecedented carnage, eviction, and hardship. Your willingness to send doctors to treat patients and injured...your determination to stand with those in need, whether through advocacy, donations, or simply raising awareness about the injustice being committed against our innocent people in Gaza, makes a real difference. Once again, thank you for your kindness, your humanity, and for reminding us that even in the darkest times, solidarity shines through."

How do we respond in solidarity?

Firstly, there is so much confusion that I suggest humble listening and being informed and even being willing to have views challenged and changed. Here are some suggestions:

- Rev Munther Isaac’s new and brilliant book ‘Christ in the Rubble’ is just out and highly recommended.

- Peter Beinart’s clear and short book ‘Being Jewish after the Destruction of Gaza’.

- Watch one of the excellent films which show the reality in West Bank such as ‘Where Olive Trees Weep’, ‘No Other Land’ or the recent Louis Theroux documentary ‘The Settlers’.

- Watch Daniel Munayer, from Musalaha video on hope. https://youtu.be/BTpKubN8j1I

- Link with others and join the movement of solidarity which includes vigils, interfaith events, professional conferences, charitable giving and engaging with elected representatives.

- We are supporting colleagues in Gaza and Sudan through Cairdeas IPCT so please consider giving generously if you are able.

- Look after one another and let us not turn away even when it is hard.

I believe God shows us the way of justice, reconciliation and peace and we trust in him for yesterday, today and tomorrow. I love this statement by Daniel Munayer whose family have been involved in reconciliation ministries in Palestine for many years.

‘People have turned hope into a means of evading responsibility and becoming passive. Hope is not optimism. Hope should not be a topic that makes us passive. Hope draws us from passive comfort into costly solidarity.’ Daniel Munayer, Musalaha.

Scenes of violence and destruction in hospital corridors

A hospital bench, where patients and staff sat, now littered with shrapnel

Meeting with Hamouda Abu Oudah, from Gaza but now in Hong Kong, at the APHC conference in Malaysia

Khamis Elessi, Cairdeas partner in Gaza, on his recent birthday

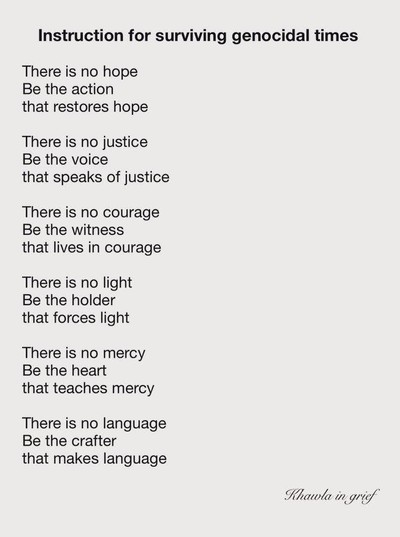

'Instruction for surviving genocidal times' by Khawla Badwan

Integration of Palliative Care in Adjumani Hospital: A Report by Vicky Opia

![]() Cameron Don

Cameron Don

![]() 31st March 2025

31st March 2025

Vicky Opia, a palliative care nurse specialist and one of our Cairdeas scholars, writes on the integration of compassionate palliative care practises into Adjumani Hospital in Uganda. Vicky takes us through the journey she and her team took, highlighting the importance of training existing staff, building relationships with district stakeholders and engaging with the community to raise awareness and reduce stigma. Vicky tells us about the impact the integration of palliative care has had on the local community, particularly for the refugee communties living in and around Adjumani, and looks to the future with intent to grow and develop palliative care services in Adjumani and beyond.

My journey: Integrating Palliative Care Services at Adjumani Hospital

As I reflect on my journey as a palliative care nurse specialist at Adjumani Hospital, I realize how much we’ve accomplished in integrating palliative care into the healthcare system here. This has been a challenging but deeply rewarding path. When I first began working in Adjumani, I quickly recognized the significant health challenges faced by both refugees and host communities. Many patients were suffering from chronic, life-limiting illnesses like cancer, HIV/AIDS, and other terminal conditions, and there was little support for their emotional, psychological, and spiritual needs.

It became clear that we needed to do more than just treat the physical symptoms of these illnesses—we needed to provide comprehensive care that addressed the whole person. That’s when I began advocating for the integration of palliative care services into the hospital's services, and over time, we began to see real changes.

Building a Foundation: Training Health Workers, Village Health Teams, and Caregivers

One of the first steps in the process was providing training for health workers, Village Health Teams (VHTs), and caregivers. It wasn’t enough just to offer palliative care services; we needed to ensure that everyone involved in the patient's care, whether in the hospital or at home, had the skills and knowledge to provide the best possible care.

Our training sessions were comprehensive, designed to equip health workers with the skills to manage pain and control symptoms effectively. We also focused on communication skills and the emotional and psychological support needed to care for patients and their families. These trainings were held at the hospital and in other community settings, including health centers in rural areas. I could see the impact of this training almost immediately as the health workers began approaching patients with a renewed sense of compassion and professionalism.

The VHTs played a critical role in the community, and we ensured that they were also trained to identify patients who might need palliative care and refer them to the hospital for more specialized care. These trainings took place in local community halls, health centers, and even remote areas, ensuring that we reached as many people as possible.

Perhaps one of the most touching aspects of the training was working with caregivers—family members or loved ones who provide much of the day-to-day care for patients at home. We taught them not only how to manage symptoms, but also how to provide emotional support and create a comfortable, nurturing environment for their loved ones. These caregivers, many of whom were exhausted and overwhelmed, now had a sense of empowerment. They could provide better care, knowing that they weren’t alone in the journey.

Seeing the Change: The Impact on Refugees and Host Communities

The impact of this work has been profound, especially for the refugees who have been displaced from their homes and are dealing with trauma, loss, and severe health conditions. Many had no idea that palliative care was even an option, and some had been suffering in silence. But with the training, both refugees and host community members began to realize that they didn’t have to endure pain and suffering without support.

As we trained health workers and caregivers, we also worked on raising awareness in the community. The stigma around palliative care has slowly started to dissipate, and more families are now open to seeking help. Patients are no longer waiting until the very last minute to receive care, and the results have been extraordinary. We’ve seen patients experience less pain and distress, and families feel more supported in their caregiving roles.

One of the most rewarding aspects of this journey has been seeing the shift in attitudes toward compassionate care. Health workers, VHTs, and caregivers are no longer just providing medical treatment—they are also offering emotional and psychological support, something that has made all the difference for so many patients and their families.

Advocacy: Bringing the District Stakeholders on Board

I’ve always believed that for any significant change to happen, it requires collaboration. In this case, the successful integration of palliative care at Adjumani Hospital would not have been possible without the involvement of district stakeholders. Local government officials, health administrators, and community leaders have been essential in ensuring that palliative care services are not only available but sustainable.

We regularly held stakeholder meetings to keep everyone aligned with our goals. Through these meetings, we raised awareness about the importance of palliative care and advocated for its inclusion in the district’s health priorities. It was through these collective efforts that we were able to secure funding, raise the profile of palliative care, and ensure that refugees and host communities had access to the care they desperately needed.

Gratitude: Dr. Mhoira and Cairdeas International

I cannot stress enough how much our work has been made possible through the generous support of Dr. Mhoira and Cairdeas International. Their funding has been the cornerstone of this initiative. Without their financial and strategic support, we wouldn’t have been able to train the health workers, VHTs, and caregivers or provide the necessary resources to support palliative care services in Adjumani. Their commitment to improving palliative care in Uganda has made a lasting impact, and for that, I am forever grateful.

Looking Forward: Recommendations for the Future

While we have made significant strides, there is still more to be done. I believe that the following steps are crucial to ensuring the sustainability and growth of palliative care services:

Ongoing Training: Palliative care is a dynamic field, and we must continue to provide professional development opportunities to health workers, VHTs, and caregivers to ensure they stay up to date on the latest practices.

Community Outreach: It’s essential to expand our outreach efforts to reach even more community members, especially those in remote areas, and educate them about palliative care and its benefits.

Strengthening Resources: We need to invest more in the resources required for effective palliative care, such as medications, equipment, and tools.

Collaboration with Other Districts: Expanding our palliative care model to other districts will create a national network of support, which will benefit even more individuals in need of palliative care.

Conclusion

Looking back, I feel a deep sense of pride in what we’ve accomplished at Adjumani Hospital. Integrating palliative care services has transformed the way we approach care for individuals facing life-limiting illnesses, and the positive impact on both refugees and host communities is undeniable. The training of health workers, VHTs, and caregivers has been pivotal, and we are now able to provide not only medical care but also compassionate support to those in need.

With the continued support of district stakeholders and organizations like Dr. Mhoira and Cairdeas International, I am confident that we can expand and enhance palliative care services in Adjumani and beyond, improving the quality of life for many more individuals in the future.

Vicky and her team

A pastor giving testimony on the benefit of palliative care

Meeting with stakeholders to discuss palliative care integration

Advocating for palliative care on the airwaves

Member of Parliament Dr. George Bhoka Didi in discussion over integration of palliative care into health facilities

‘Let the Sky be Your Limit’: Compassionate Leadership Fellowship 2025

![]() Cameron Don

Cameron Don

![]() 13th March 2025

13th March 2025

Hello to all our supporters, my name is Cameron and since October I have been the Operations Director at Cairdeas. This has been a busy and exciting time and I’d like to thank all the Cairdeas team for making the transition as smooth as possible. In February, I was given the opportunity to travel to Kerala, India with Cairdeas to help run the final week of the Compassionate Leadership Fellowship (CLF). This has been a year-long program of teaching and mentorship for palliative care clinicians from India, Nepal, Kenya and Rwanda, aimed at developing their leadership skills and achieving personal learning growth. Dr Mhoira and Dr Chitra have been working so hard all year as course coordinators and it was a great privilege to be brought in to help with this last module.

After a couple of days shaking off jet lag and getting used to the Indian heat, we travelled to Thiruvalla, where the course would be taking place at Believer’s Church Medical College Hospital (BCMCH), one of our partner organisations in India. Before the module week began, I was given the chance to join the palliative care team at BCMCH as they made their morning rounds. This was an illuminating first look at healthcare in foreign context for me, and the team discussed with me the importance of spiritual support in their palliative care, as part of their care for the patient’s ‘total pain’, encompassing physical, spiritual, emotional and psychological pain. We also spent time discussing the roles of families in patient care, and the difficulties this can present when clinicians’ and families’ priorities do not align, e.g. a family not wishing a doctor to tell a patient they have cancer to protect their emotions.

On the eve of the course I started to meet the mentors and fellows who had travelled from near and far for the CLF. I had been nervous about this trip and joining a group of people I had never met before, but this quickly disappeared as I was welcomed in so warmly by all. My role during the week was partly IT, partly logistics and a good amount of problem solving, all aimed at keeping everything running smoothly to facilitate teaching and learning.

The CLF utilises a variety of teaching styles to allow all fellows to learn in their way, having spent time during Module 1 using tools such as Myers-Briggs, KELP and LPI to allow self-examination and recognition of one’s own learning style. Group tasks throughout the week highlighted the varying styles of the fellows; some were very reflective, considering problems and imagining solutions before they acted, others were highly active, launching into tasks and solving problems as they went. It was fascinating to observe the interplay between these styles in group settings and how the fellows managed their different ideas of how to approach a task. I was able to take part in some tasks and landed slightly more on the ‘think first, then act’ side of the equation. It’s a great strength of the CLF program that fellows are first forced to look at themselves and their own learning and leadership style before moving on to teaching practical skills, allowing for richer understanding of their strengths and weaknesses when approaching a task.

After a year of getting the know one another, the bonds between the fellows and mentors, and the fellows with each other, was tangible, buoyed by their knowledge of each other’s learning styles and personality types. Tasks were frequently discussed retrospectively (often over wonderful Kerala cuisine), with fellows examining who had thrived or found themselves outside their comfort zones. The transformational growth the fellows have experienced over the year was highlighted by the willingness to jump into tasks that were outside of their comfort zone. For example, Biju, a kind and reserved fellow, took on the role of a hard-lined medical director facing disgruntled employees during a role-playing negotiation exercise. The fellows continually spoke about the growth and development they saw in themselves owing to the CLF, and it was heartening to see the fruits of the hard work put in by the CLF team to plan, fund and organise this course over the past few years.

Having developed their understanding of the characteristics of leadership and understanding oneself as a leader in the previous modules, this module focused on developing practical skills to allow the fellows to put their understanding into practice and become changemakers in compassionate care. Throughout the week, mentors provided expert teaching on strategic planning, circles of influence and control, negotiation skills, presentation and public speaking skills and the use of storytelling and AI in social media marketing. Fellows were presented with tasks ranging from planning grant applications for palliative care facilities in rural Nepal to negotiating a price for stolen (and imaginary!!) iPhones. Fellows were also given the chance to review their leadership development over the past year and make poster presentations on their growth, which were displayed in the entrance lobby at BCMCH. The wide range of skills the fellows gained throughout the week will serve them well as they go back into their work lives and strive to be compassionate leaders in palliative care. Strategic planning was a particularly eye-opening session, with plans to change the world found to be constrained by budget, time and attainability. It will be exciting to see the journeys our CLF family go on in their careers, and their communities will be truly blessed to have such committed, hard-working, caring and compassionate leaders in their midst.

The week culminated in the valedictory ceremony, where the fellows each had a chance to speak and present about their personal and professional journey and growth, over the past year and their lifetimes. This was a beautiful and emotional morning of sharing between friends and colleagues; stories of hardships and disappointments, overcoming challenges and achieving dreams. Sharing personal stories was the final glue which truly connected the group on an intimate level and there were more than a few tears shed. The whole CLF family spoke of what a powerful and inspiring time they had together, and took home with them memories, friendships and leadership skills for life.

I want to truly thank Dr Mhoira and Cairdeas for inviting me to be a part of such a wonderful and memorable two weeks, and to all the fellows and mentors of the CLF for welcoming me into their family. It was a fantastic experience which will serve me well for many years to come, both through the teaching of the CLF mentors and the experiences of traveling and working in an international context. The CLF is a fantastic program with passionate, knowledgeable people behind it and I can’t wait to see what the future holds for our fellows and for the communities they serve.

Special thanks go to all of our partners who helped to make the Compassionate Leadership Fellowship possible: Believers Church Medical College Hospital (BCMCH), Cairdeas International Palliative Care Trust (Cairdeas IPCT), Global Health Academy, University of Edinburgh (UoE), the Indian Association of Palliative Care (IAPC), and RMD Trust.

A morning with the BCMCH palliative care team

A group discussion on circles of influence and control

Biju's birthday cake!

Lunch at Mango Meadows, served on a banana leaf

The CLF family on valedictory day