Blog: Voices of indigenous peoples: ‘connectedness, interdependence, and sharing in the celebration of life in community’

![]() Dr Mhoira Leng

Dr Mhoira Leng

![]() 13th October 2022

13th October 2022

This blog was orginally published by the Indian Association of Palliative Care, IAPC, on 25th August 2022.

For too long the voices of indigenous people the world over have been relegated to the margins. Our focus as a global community has been on progress which is all too often measured in economic development, an emphasis on a biomedical view in scientific thinking, a desire for cure at all costs in chronic illness management and the emphasis of the individual and their society over another.

Streams of ancient wisdom, rich culture and deep spirituality have been passed over or even actively suppressed. As our world faces the existential threats of climate degradation leading to a perfect storm that endangers the health of our planet with the health or flora and fauna and of course the health of each person. [i] Our global consciousness seems to be finally waking up to these dangers and broadening its scope to hitherto less regarded sources of wisdom and ways of being that may help achieve a paradigm shift in perceptions and actions.

It is time to consider how we can transform our way of living and being before it is too late for the health of our planet, our peoples and ourselves. Perhaps the global community more than ever needs to listen to the voices of indigenous peoples. Perhaps in the global palliative care community, where we are so aware of the need for active listening, we can ensure this includes the experience and wisdom of indigenous peoples.

Marginalisation and separation

In most of our world indigenous peoples, at times known as primal or tribal peoples, have shown incredible resilience to survive and even thrive despite lack of sovereignty, environmental degradation that has affected them disproportionately added to the lack of political voice or rights to their ancestral land. [ii] Despite the UN Charter on the rights of indigenous peoples ‘affirming that indigenous peoples are equal to all other peoples’ this is very often not the reality. [iii]

If we take the example of the North East of India there is a geographical challenge of the terrain and the lack of transport networks added to the lack of political determination despite indigenous peoples in several states being the majority of the population. Food, dress, language, culture, identity all are very different to other parts of India and while some indices such as education and literacy are far higher, others such as opportunity and self-determination are much less. Further south, in Wayanad, Kerala, we see ways of living offered to tribal peoples but not co-created with little understanding of their link to land and ongoing struggles for recognition. [iv]

Interestingly, this ‘marginalisation’ may also be a world view since many indigenous or tribal groups identify strongly with their setting and land. They are in fact at the centre of their homeland and it puts the rest of us at the margins. [v]

This link with land is far more than just geography and includes a deep inter-connectedness which can still be seen in the protection of biodiversity and ability to live in harmony with ‘mother earth’. Yet globalisation, colonisation and attempts at ‘civilization’ have led to culture, language, traditional beliefs and wisdom has been side-lined or even suppressed, displacement leads to loss of traditional ways of living, loss of vital ecological knowledge, lack of access to traditional medicines and loss of livelihoods often with social stigmatisation and isolation. All of this leads to a generational impact.

There is a wider impact which is increasingly being understood in terms of the health of our planetary environment and people. [vi] We have heard the cry of ‘nihil de nobis, sine nobis or nothing about us without us [vii]’ from people groups such as HIV/AIDS and disability activists but this needs to also include indigenous peoples whose experience is so often projects and care ‘done to them’ even by those who seek to help. What does this mean for how we develop and deliver palliative care and in who and how we engage in the community? What does it mean for our understanding of what constitutes holistic context of palliative care where a person beliefs, culture, community, connectedness, faith, hopes and fears are inextricably intertwined with their physical, socioeconomic and psychological experience?

‘No man is an island…never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee [viii]’. no matter how much we slide into an individualistic or even nationalistic worldviews the truth of our common humanity is clear to see. We see the dangers of this narrow worldview in relation to climate degradation and the deep inequalities in our world with the resultant harm to each person are being exposed. Our world has recently experienced the COVID19 global pandemic. As vaccines became available in record time the global community had a decision to make. Would the relationships that links us, particularly in the era of infectious disease and global travel, lead to a deeper realisation that what affects one person and one nation affects all or would this drive a wedge based not on global health but on national interest. Antonio Guterres, UN secretary general, summed this up when he reprimanded the world for the inequitable distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, describing it as an “obscenity” and giving the globe an “F in Ethics [ix].” He spoke to world leaders of the images from some parts of the world of expired and unused vaccines in the garbage; with the majority of the wealthier world immunised while more than 90% of Africa has not even received one dose. He suggests “At this critical moment, vaccine equity is the biggest moral test before the global community [x].”

Perhaps listening to the wisdom of indigenous peoples is a crucial part of the paradigm shift that is needed in planetary health and palliative care.

Interconnectedness

At the heart of this shift is the urgent need to move away from a perspective which sees the individual as the most important with our relationship to the earth as something we can use and subjugate and instead turn to ancient ways of thinking where we realise the inter-connectedness of each person and each part of the planet in which we live. Two concepts from Southern Africa and from North East India offer an insight into how interconnectedness can be a transformational influence on societal and individual thinking and being and so in turn impact on our thinking and practice for palliative care.

Ubuntu is an Nguni word and represents a concept common in Southern African Cultures. It speaks of our common humanity and the understanding that we are who we are through our connectedness with others. It is sometimes represented as ‘I am because we are’.

Archbishop Desmon Tutu explained the concept ‘My humanity is caught up, is inextricably bound up, in yours. We belong in a bundle of life. We say a person is a person through other persons [xi]’. Again Barak Obama spoke of Ubuntu at the funeral of Nelson Mandela saying the spirit of ubuntu is a “recognition that we are all bound together in ways that are invisible to the eye; that there is a oneness to humanity; that we achieve ourselves by sharing ourselves with others, and caring for those around us [xii].”

This common humanity, equality and inherent value is at the heart of palliative care and has helped to inform and transform thinking about the culture and context of palliative care in many settings. In children’s palliative care ‘ubuntu’ can help with the transitions from health to illness and survivorship. It can also ensure the child as well as the adult remains connected to society and address the profound dislocation, alienation and isolation that people living with or affected by serious health related suffering can experience.

Ubuntu also has relevance to the living networks of community members, carers, health and social care workers and policy makers advocating for palliative care. This can be seen in many declarations of and for palliative care including the ICCPN statement of 2005. ‘As a community of palliative care practitioners we recognize that disparities exist within and between countries and services, but collectively we are a rich resource of knowledge, skills and judgment; and we commit to share all that we can to achieve this joint vision [xiii].”

Khankho was the underpinning to traditional Kuki life and offered grounding, sustaining and direction to this primal or tribal society based in the North East of India; now mostly in Manipur. ‘Life was seen as interdependent, relational and inclusive and was shared in a community expressed through integrity, honesty, love, justice, fairness and selfless service of one another [xiv]’. This led to a scared and high view of human life which turn evolved ways to relate to one another including the management of conflict or transgressions and how to live in harmony with the natural world. The word itself is derived from khan ‘to grow or behave’ and kho ‘sensibility or awareness of ones surroundings’.

Dr Haokip is the founder and director of Bethesda Khankho Institute in Manipur working with indigenous communities and teaching contextual theology in relation to indigenous knowledge and traditions. He writes of the challenge of trying to define Khankho using concepts form our modern systems of thought and being. He says ‘Khankho is leading a life in tune with the culture grounded in love, care, fairness and justice. It expresses connectedness, interdependence and sharing in the celebration of life in community.’

This crucially extends to what we often refer to as the natural world. It is seen as a ‘living world infused with spirit and so capable of knowing joy, pain, distress and hope.’ An example given are the rice plants which is seen by the farmer as a living things requiring care and bad words should not be spoken against them. This is in direct contrast to the concept of subjugation of the natural world and exploitation of resources.

The work of the Bethesda Institute is having a direct bearing on all aspects of community life including health care, chronic illness and holistic palliative care. There has been an initial discussion of how palliative care can be understood and support offered through the concepts of Khankho during a visit by the author.

It also shows how a traditional wisdom can change our understanding of theology and spirituality and the need for very different ways of understanding our traditional palliative care domains. When we examine our understanding spirituality the concepts of meaning, belonging, value, purpose, forgiveness, hope, presence, transcendence are central. Our understanding of spirituality in palliative care can be transformed and informed by insights from indigenous wisdom.

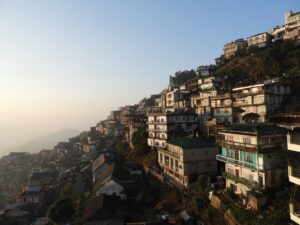

Mizoram, one of the most remote and difficult to access states in North East India, also has one of the highest tribal populations; mostly the Mizo people. The author has observed the way inter-connectedness is a reality in the development of palliative care. Traditional ways of being are deeply linked to Christian faith practices and located in the community locality. In Aisawl, the capital city set high on the beautiful foothills of the Himalayas, when a person dies a bell is rung and the community respond. The young people (Young Mizo Association members) start to organise what is needed, members come to sit with the bereaved and offer support, both practical and spiritual. News is shared quickly including via media. Members of this community habitually meet daily for prayers and so needs are attended to through that tight and interconnected structure. When we sought to discuss the concept of volunteering in palliative care as seen in other parts of India such as Kerala, it became clear their society already had a deeply held and societal means of support that could be the medium for palliative care support and end of life care.

Compassion

Flowing from our interconnectedness to one another and our planet is compassion. It is a natural outworking of truly seeing and experiencing our common humanity, being impacted and moved by the experience of others and stirred to making a difference. This journey is a daily experience in our palliative care movement as we listen to the stories and motivations of those with palliative care needs alongside our colleagues and pioneers. MR Rajagopal, often referred to as the father of palliative care in India, explores this in his recent memoir has the poignant title ‘Walk with the weary : Lessons in humanity in health care [xv]’.

In the introduction to the Sustainable Development Goals [xvi] it says “if we realize our ambitions across the full extent of the Agenda, the lives of all will be profoundly improved and our world will be transformed for the better”. The document was entitled ‘Transforming our World’ and should not be seen as a list of separate goals but rather an interconnected and integrated roadmap that helps us coordinate a global response. The transformational and compassionate nature of this ground breaking approach can be seen in such terms in the document such as ‘healing of the nations’ and ‘leaving no one behind’.Liz Grant, a global leader in planetary health and compassion thinking, states that ‘compassion is the glue that holds the sustainable goals together [xvii][xviii].’

Compassion as an essential paradigm in global health and crucial to achieving quality health care. Sham Syed has penned this equation for our time.

Awareness + empathy + action = compassion. [xix]

Compassion is also a crucial component as a key indicator of quality outcomes in a health care system. This has particular relevance for marginalised or fragile communities and is in important in the development of a different approach for health leadership [xx].

Listening to voices and experiences of indigenous peoples helps us to an understanding of compassion which encompasses, is informed by and transformed through indigenous wisdom. It can help us understand how we can develop and demonstrate compassion for each other, for our world, for those on the margins of society and for ourselves. It is that from that deep value and transformational force that is compassion that we can start to re-discover our common humanity, the value of each person and perhaps begin to listen to those so often overlooked. In compassion we can discover a dynamic way of responding to the needs of others and to the burden of health related suffering and environmental degradation we are experiencing.

Our global community has affirmed ‘that all peoples contribute to the diversity and richness of civilizations and cultures, which constitute the common heritage of humankind.

In Voices from the Margins Jangkholam Haokip and David Smith state ‘There is a growing realisation that recurring economic and social crises across the world threaten the very survival of the earth in all its beauty and variety, and that the wisdom embedded in ‘indigenous knowledge’ has something vital to offer….to broader debates in religious, ecological, social and political issues in the era of globalisation [xxi]‘.

Perhaps it is this community heritage that must be recognised, valued and its wisdom allowed to influence and shape our world and its peoples today and to be a fulcrum for greater understanding and deeper compassion in our palliative care community as we actively listen.

References

[i] UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar5/

[ii] Redvers, Nicole et al The determinants of planetary health: an Indigenous consensus perspective Lancet Planet Health 2022; 6: e156–63

[iii] United Nations declaration on the rights of Indigenous Peoples. Sept 13, 2007. https://www.un.org/development/desa/ indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf (accessed March 20, 2021).

[iv] https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/tribals-in-wayanad-wait-for-the-promised-land/article19743621.ece

[v] Fabian Lyngdoh. The inculturation of Christianity among the Khasi people of Meghalaya State. Chapter in Voices from the margins; wisdom of Primal Peoples in the era of World Christianity Ed Jangkholam Haokip and David W Smith ISBN:978-1-83973-534-9

[vi] Redvers Nicola. The Value of Global Indigenous Knowledge in Planetary Health. Challenges 2018, 9, 30

[vii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nothing_About_Us_Without_Us

[viii] John Donne 1672-1631 Accessed https://www.poetry.com/poem/22559/no-man-is-an-island

[ix] Guterres A. UNITED NATIONS address. Sept 21

[x] Press release United Nations 17th Feb 2021

[xi] Tutu D. No future without forgiveness.Image Pressworks, Portland, OR2000 https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/12/10/remarks-president-obama-memorial-service-former-south-african-president

[xiii] International Children’s Palliative Care Network statement on paediatric palliative care.South Korea, Seoul2005 (Available at:) www.icpcn.org

[xiv] Towards a Kuki contextual theology of Khankho. Jangkholam Haokip.Chapter in Voices from the margins; wisdom of Primal Peoples in the era of World Christianity Ed Jangkholam Haokip and David W Smith. ISBN:978-1-83973-534-9

[xv] MR Rajagopal ‘ Walk with the weary : Lessons in humanity in health care’ Notion press Feb 2022 ISBN:B09WKL2K56

[xvi] Transforming Our World; the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. United Nations 2015 https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/

[xvii] Grant Liz at al. A compassion narrative for the sustainable development goals: conscious and connected action. The Lancet, Volume 400, Issue 10345, 7 – 8

[xviii] Liz Grant. Global Health Academy University of Edinburgh. Supporting Planetary Health and the Sustainable Development Goals https://www.ed.ac.uk/global-health/sdgs-and-compassion

[xix] Shams Syed, Unit Head, Quality of Care , WHO https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=39G72FZ4Fb0 Global health Compassion Rounds Task Force for Global Health Emory University

[xx] Quality of care in fragile, conflict-affected and vulnerable settings: taking action16 December 2020 WHO https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015203

[xxi] Introduction in Voices from the margins; wisdom of Primal Peoples in the era of World Christianity Ed Jangkholam Haokip and David W Smith ISBN:978-1-83973-534-9

Dr Mhoira discussing palliative care in a traditional Kuki meeting place, Manipur.

Aisawl, Mizoram.

Ubuntu Ceremony Creed in South Africa that a universal bond unites humanity.

Traditional culture of Mizoram.

Mountains of Mizoram.